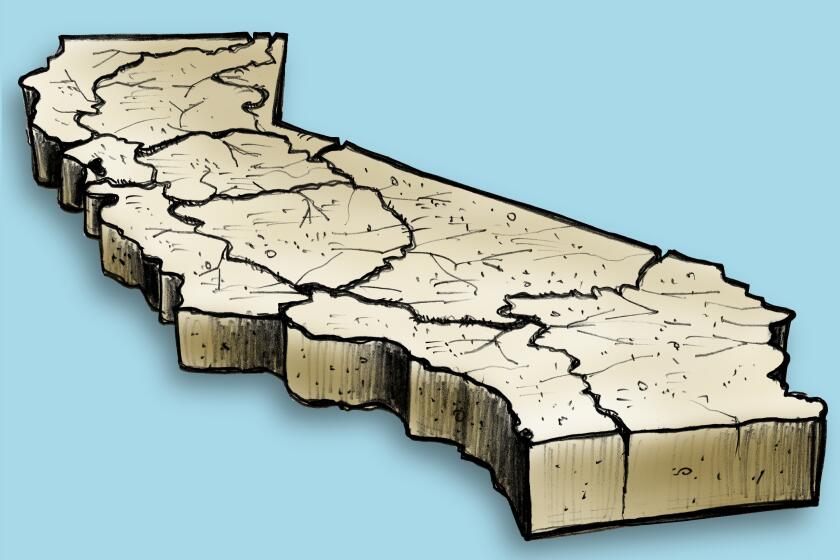

California is now practically drought-free, but we keep wasting

so much rainwater

Almost all of California is finally drought-free, after Tropical Storm Hilary’s rare summer drenching added to this winter’s record-setting rainfall totals.

But despite all that drought-busting precipitation, California continues to capture only a percentage of that water. Much of the abundance in rain from Hilary ended up running off into the ocean — not captured or stored for future use, when California will inevitably face its next drought.

“We’re not even coming close to capturing all the runoff,” said Mark Gold, the director of Water Scarcity Solutions for the Natural Resources Defense Council. He still called Hilary’s rainfall “an unexpected boon” for Southern California’s local water supplies, but said too much of the storm’s water washed away — the latest reminder of the state’s urgent challenge to better capture rainwater to help refill vital groundwater resources.

“The potential is really there for us to do even better,” Gold said. “We can definitely do a lot more than what we’re doing.”

Following the torrent of winter storms from a parade of atmospheric rivers, much of California pulled out of drought conditions after three of the state’s driest years on record. And Hilary continued to build on that trend — pulling one of the state’s driest regions out of such dire conditions.

“Most of that lingering drought ... has been essentially removed from the Mojave Desert,” said David Simeral, a climatologist at the Desert Research Institute, who mapped the latest U.S. Drought Monitor update. While much of the state moved out of drought conditions after strong winter and spring atmospheric river storms, Simeral said the Mojave didn’t benefit as much from those rainmakers.

But after Hilary dumped 2 to 6 inches across the Mojave, “it was enough to be able to remove the remaining areas of drought,” he said. The Mojave had been in drought conditions since August 2020.

Only California’s most northwestern and southeastern corners remain under moderate drought or in abnormally dry conditions — just 6% of the state, according to the drought monitor.

State and local officials have been actively working to improve methods to capture stormwater, but it’s simply not been fast enough to keep up with growing water demands in a more extreme climate — while balancing flood control. Los Angeles County recently shared its latest water plan, which includes lofty goals to greatly increase yearly groundwater recharge.

But when fast, strong storms like Hilary currently hit, the local infrastructure isn’t able to capture a majority of the deluge.

“What that means is that there’s larger amounts of rainwater rolling down the hill, rolling down to the street ... our systems are getting flooded and overwhelmed pretty quickly,” said Art Castro, a watershed manager for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. He said that happened during Tropical Storm Hilary at the Tujunga Spreading Grounds — one of the county’s larger spreading grounds, which employ earthen bowls to capture runoff and encourage the rain to percolate into the earth, recharging important aquifers.

When the basins are full, the water will just “bypass the system,” Castro said, running off into the Pacific.

Still, the city was able to capture more than 10,000 acre-feet of water from Hilary’s rainfall, as of preliminary numbers last week, with more expected as water continues to be diverted from regional dams, Castro said. That’s about 3.2 billion gallons, enough to provide a year’s worth of water to 40,000 households, he said.

However that 10,000 acre-feet only makes up about 7% of the water the city has captured since October, Castro said.

“In a perfect world, we should have captured a lot more than 10,000 acre-feet because of Hilary,” Castro said. “But because of the limitations of our infrastructure ... we weren’t able to maximize that potential.”

And maximizing that water is increasingly important for L.A., as drained aquifers cannot just bounce back after one good water year.

“What we need to do is either capture a lot of the wet season, or develop more stormwater recapture projects that can take advantage of an average year,” Castro said. That will likely require “back-engineering” of L.A.’s water system, he said, as much of it was designed with older rain models in mind, when storms weren’t as intense.

County-operated spreading grounds, of which there more than two dozen, captured approximately 8,600 acre-feet of stormwater during Hilary’s storms, about 2.8 billion gallons, according to L.A. County Public Works spokesperson Steven Frasher. But in this above-average rainfall year, that amounts to less than 2% of the county’s stormwater captured since October.

On a statewide level, Hilary also didn’t have a major effect on water supplies.

“This was a very fast moving storm and, really, it was largely a Southern California event,” said Jeanine Jones, the interstate resources manager for the California Department of Water Resources. “It caused a lot of flash flooding in places that aren’t designed to handle a lot of water, like Death Valley and some of the desert areas, but from a water supply perspective, it’s not really very significant.”

Most of the state’s reservoirs, and its largest, are located in northern California, which meant they were largely unaffected by the southern tropical storm, Jones said. And, perhaps more importantly, most of those reservoirs already sit at some of the highest levels in years, many measuring well above 100% of historical averages, state data show.

“We got a lot of water all at once in a really short time, but it wasn’t the kind of storm that does much for water supply,” Jones said.

The ground can only absorb so much moisture so fast from such quick, intense storms, like Hilary, Jones said.

“The groundwater takes time to recharge,” Jones said. “Most of that water is going to run out to the ocean or run into a desert playa.”

But in the short term, officials are hopeful the rainfall from the unusual tropical storm will help with one thing: wildfires.

“It should help some in terms of adding some soil moisture and helping the plants to not be so dried out,” Simeral said, which creates less fuel for flames.

Forecasters typically expect September to begin the peak of Southern California’s fire season, but the recently added moisture could help delay that, said Rose Schoenfeld, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard.

“Hopefully this extra precipitation will push that back even further,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment